After about a month off finding an apartment and moving, here’s a topic I’ve been thinking about for a few years.

Unconscious Drives in Rav Soloveitchik’s Writings

An underrated phenomenon in Rav Soloveitchik’s thought that he appeals to with surprising regularity is what I would call “unconscious drives.” He does not use this language (and has choice words for Freud in an essay in Out of the Whirlwind), but it accurately captures the dynamic I want to lay out here. I touched on this in the discussion of faith in my Tradition essay on R. Soloveitchik (and I’ll return to that topic below), but it’s worth laying out some of the different examples of what I mean.

First, a basic definition. When I say, “unconscious drives,” what I mean is that Rav Soloveitchik depicts individuals or movements (made up of individuals) as acting based on motivations of which they are unaware, and/or which differ from what they would take to be their motivations. To make up a banal example, if you asked a person why they eat pistachio flavored ice cream, they might say it’s because they like the flavor, but it could really be because their sadly-departed parent loved pistachio-flavored ice cream, and eating it gives them a sense of their lost parent’s presence. Psychoanalysis often differentiates between desire and drive as elements of psychic life, but for all purposes we’ll ignore that distinction and just refer to the phenomenon of individuals or movements acting based on motivations of which they are unaware.

As one more introductory note, I should say that this idea might already have some purchase in Judaism in the idea of the yetser hara, the “evil inclination.” This isn’t the place to explore that further, but for Rav Soloveitchik there’s a lot to say on if and how he accepts that idea. The best place to look for something similar to our topic in this post is his essay “Catharsis,” throughout, but particularly the last section, which focuses on “catharsis” in the context of religion.

The Unconscious Quest for God

As a first, and quite explicit, example from Rav Soloveitchik’s writings, let’s look at his 1973 speech, “Majesty and Humility.” The essay lays out two forms of human existence, each associated with one half of the title, and argues for a variety of implications of each, and their combination. For our purposes, we should just note that he sees each form of life as relating to God—and thus also finding God—in very different ways. Majestic man finds God in exploring the cosmos, and Humble man finds God in experiences of suffering and finitude. However, Rav Soloveitchik does not insist that this “quest for God” is a conscious, intentional activity: “Both cosmos-conscious man and origin-conscious man quest for God, although they are not always aware of this quest.” When secular, Enlightenment-era philosophers and explorers were mapping the world and writing philosophical treatises, they likely wouldn’t have called that a quest for God. But Rav Soloveitchik would have.

A similar dynamic appears in Rav Soloveitchik’s “early” work, And From There You Shall Seek (I have thoughts on calling it “early” but that is for another post). In this phenomenological work (meaning it does philosophy/theology by attempting to describe human experience/consciousness), R. Soloveitchik lays out different elements of human consciousness as related to the quest for/relationship with God. He argues that the quest for God is a basic part of human nature, one which takes a variety of forms over the course of human history:

“Seeking God through the external and the internal worlds is not a theological issue of interest only to scholars of religion. It is a fundamental problem that arose at the dawn of human culture. From the time of the Greek philosophers to that of the masters of modern philosophy (not to mention the sages of the theocentric Eastern cultures), the search for God has resounded throughout the intellectual world. It takes different forms in accordance with the historical and cultural peculiarities of each epoch; it conceals and disguises itself in the range of concepts and variegated aspects through which each generation expresses its thoughts and internal struggles, but it never disappears entirely from the horizon of inquiry.” (8–9)

Now the first half of this paragraph might just mean that different cultures have imagined God differently when they have searched for God. Critical for our purposes is the sentence: “it conceals and disguises itself in the range of concepts and variegated aspects through which each generation expresses its thoughts and internal struggles.” The search for God manifests differently in the dynamics and thoughts of each generation in a concealed form. They might not know it, but they are searching for God. This fits well with the rest of the chapter from which the chapter is taken where the quest for God (explicitly framed as such) takes the form of the quest for real reality, for something absolute and non-contingent, by way of sense experience and potentially science, though science is ultimately said to be misleading and unhelpful in this regard.

A similar dynamic, though perhaps different in some important ways, shows up in The Halakhic Mind, where R. Soloveitchik describes the desire to know reality as exactly that: “Every metaphysical quest for reality is driven by the urge for finality and totality which neither scientific microscope nor telescope can reveal” (19). Knowledge is rooted is desire, rather than the other way around.

I should note that this aspect of R. Soloveitchik’s theory of knowing (and the relationship between these two books) is well discussed in Alex Ozar’s JQR article, “Joseph Soloveitchik as a Weimar Intellectual,” though the above quote is accidentally attributed to And From There You Shall Seek rather than The Halakhic Mind (and I disagree with some of Ozar’s conclusions about R. Soloveitchik’s politics). William Kolbrener’s article, “On Abandoning Aristotle: Love in Psychoanalysis and Jewish Philosophy,” is also good on this, if I recall.

Let’s turn now to his interpretation of Zionism, specifically, secular Zionism. Rav Soloveitchik’s famously uses a dichotomy between the covenants of Egypt and Sinai (parallel to his concepts of Fate and Destiny) to at once connect and distinguish between secular and religious Zionism—both secular and religious Zionism are concerned for the Jew’s bodily well-being (Egypt/Fate), but only the religious Zionists are concerned with their spiritual destiny (Sinai). Setting aside questions about the utility of this claim, let’s just note that he has a clear idea of secular Zionism as a movement fully explainable by its own rational-utilitarian motivations.

It’s therefore quite surprising that you can open up The Rav Speaks and find him presenting a very different understanding of secular Zionism’s motivations:

“As stated above, one acquires a share in the Creator of the universe only by building an altar, by “you shall seek . . . when you search with all your heart and with all your soul” (Deut. 4:29). All effect that mode of possession — the observant Jew consciously and the secular Jew unwittingly. We observant Jews believe that every Jew is forever seeking the Creator of the universe, unwillingly or willingly, inadvertently or intentionally. He seeks Him even when he protests that he does not need Him. Of course, fortunate is the Jew who knows Whom he is seeking and toward Whom his soul yearns. I pity those Jews driven by an inner force toward the Creator of the universe, who exert themselves to repress that yearning. This stubborn denial of the Creator of the world, despite man’s instinctive longing toward Him, is the cause of many emotional and spiritual disturbances and confuses the mind and heart. Yet one cannot change the fact that the more the secular Jew proclaims that he has no relationship to sanctity, the more he feels in the innermost recesses of his heart that he has given false testimony about himself.” (21)

Here too we have the quest for God as an unconscious drive, but where before the actions which this drive motivates were exploratory and philosophical, here the discussion is about secular Zionists’ willingness to sacrifice for the Jewish settlement of the land of Israel. This activity, which could be interpreted in mere utilitarian terms, or as a secular-transcendent act of nationalism, is actually a manifestation of an unconscious, perhaps even suppressed, desire for the “God of Israel” (22) (notice the nationalism sneaking in the back door). Their desire for the land is actually a desire for God.

Relatedly, and leaning into the subtle nationalism of the last piece, is the very concluding paragraph of the book of essays/lectures, Halakhic Morality (Maggid Books, 2017):

Every Jew has a capacity for repentance and a desire for sanctity. Quite often, it is subconscious, hidden away in the deep recesses of his personality of which he is not aware. No alienated Jew may be expelled from our society, for we have never given up on a single Jew or considered him completely lost. With patience and tolerance, we may bring him back if we are generous, if we have faith in him. (222)

This is part of a passage with a direct parallel in one of Rav Soloveitchik’s teshuvah speeches, “The Individual and the Community” (On Repentance [Maggid Books, 2017], 39–62, particularly 58–62), which has been discussed by Daniel Hershkovitz in his article on Rav Soloveitchik and German Nationalists, and Gerald/Yaakov Blidstein’s article on the Jewish People in Rav Soloveitchik’s thought (originally published in Tradition, then in Hebrew in a collected Avi Sagi volume, then in Society & Self, a collection of Blidstein’s essays on R. Soloveitchik). In both passages, Rav Soloveitchik argues that a Jew is required to believe in the Jewish People, which means believing that all Jews will someday do teshuvahand live their lives in accordance with Orthodox Jewish law. The quest for God here isn’t manifest as an ostensibly secular practice, rather it is posited as a fact which necessitates acting toward certain Jews as if they believed even if they seem not to do so.

The Lonely Man of Faith and the Drive to Be Fully Human

Armed with these examples, let us turn for our last two examples to one final text: The Lonely Man of Faith. While fairly popular and well-known, I still think this text is wildly underrated. It’s a rich text that, if I were to try to sum it up, is not about a Jew’s individual religious life so much as different conceptions of human nature and the connective tissue binding individuals into (different kinds of) communities.

The basic structure of the book is an exploration of two imagined figures, “Adam the first” and “Adam the second,” loosely based on the first two chapters of Bereshit and essentially parallel to the “majestic” and “humble” archetypes from “Majesty & Humility” we saw above. At the end of chapter I, laying out the basic dynamics of Adam the first, R. Soloveitchik remarks that

“It is God who decreed that the story of Adam the first be the great saga of freedom of man-slave who gradually transforms himself into man-master. While pursuing this goal, driven by an urge which he cannot but obey, Adam the first transcends the limits of the reasonable and probable and ventures into the open spaces of a boundless universe” (Maggid, 2018; 15)

Much as R. Soloveitchik said Majestic man is driven to explore by an unconscious drive to find God, so too Adam the first is driven to explore and dominate by an urge which determines his conduct even beyond his ability to decide or rebel against it.

R. Soloveitchik makes much the same remark a few pages later, this time regarding both Adam the first and Adam the second.

“Both Adams want to be human. Both strive to be themselves, to be what God commanded them to be, namely, man. They certainly could not reach for some other objective since this urge, as I noted, lies, in accordance with God’s scheme of creation, at the root of all human strivings and any rebellious effort on the part of man to substitute something else for this urge would be in distinct opposition to God’s will which is embedded in man’s nature. The incongruity of methods is, therefore, a result not of diverse objectives but of diverse interpretive approaches to the one objective they both pursue.” (19)

The language of “urge” returns here, and the object of this urge is made explicit: to be human. The creator embedded this urge within human nature, and it causes people to act in certain ways. People then explain to themselves why they do what do, but their interpretations may be undermined by the raw fact of the urge. Any instrumental explanation (this is the critique of ch. IX, and perhaps the main critical point that the book makes) necessarily fails to appreciate this simple, brute reality. Any motivation that the Adams might give for their behavior, particularly if it takes the form of “I do X to attain goal Y,” is necessarily false. The only fully honest explanation is “I do X because I feel driven to do X,” and perhaps, “Doing X is part of being human.”

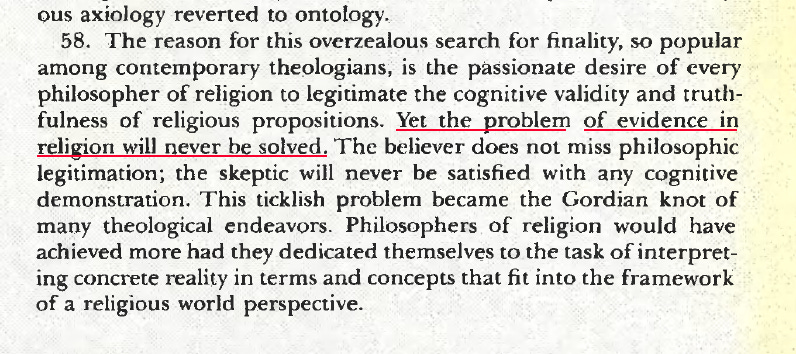

This line of thought reaches its peak in the description of faith in ch. IX, which is worth quoting at length:

“the man of faith is not the compromising type and his covenantal commitment eludes cognitive analysis by the logos and hence does not lend itself completely to the act of cultural translation. There are simply no cognitive categories in which the total commitment of the man of faith could be spelled out. This commitment is rooted not in one dimension, such as the rational one, but in the whole personality of the man of faith. The whole of the human being, the rational as well as the non-rational aspects, is committed to God. Hence, the magnitude of the commitment is beyond the comprehension of the logos and the ethos. The act of faith is aboriginal, exploding with elemental force as an all-consuming and all-pervading eudaemonic-passional experience in which our most secret urges, aspirations, fears, and passions, at times even unsuspected by us, manifest themselves. The commitment of the man of faith is thrown into the mold of the in-depth personality and immediately accepted before the mind is given a chance to investigate the reasonableness of this unqualified commitment. The intellect does not chart the course of the man of faith; its role is an a posteriori one. It attempts, ex post facto, to retrace the footsteps of the man of faith, and even in this modest attempt the intellect is not completely successful. Of course, as long as the path of the man of faith cuts across the territory of the reasonable, the intellect may follow him and identify his footsteps. The very instant, however, the man of faith transcends the frontiers of the reasonable and enters into the realm of the unreasonable, the intellect is left behind and must terminate its search for understanding. The man of faith, animated by his great experience is able to reach the point at which not only his logic of the mind but even his logic of the heart and of the will, everything—even his own “I” awareness—has to give in to an “absurd” commitment. The man of faith is “insanely” committed to and “madly” in love with God.” (79–80)

Faith is defined as a fundamental “commitment” which undermines rationality, intentionality, and the sense of self (tracking this language of “commitment” in R. Soloveitchik’s writings is more fruitful than look for “Faith” or the like, in my experience; for example, see throughout Halakhic Morality). The person of faith can at most interpret and attempt to explain to themselves their fundamental commitments, but they cannot choose those commitments, and the commitments are not necessarily rational. To have faith is to have this unconscious commitment, directed at God specifically, without which the person would be all surface and no depth. “The whole of the human being” is a complex of elements including both the conscious mind and the unconscious commitments which move it.

Reflections

What does all this mean? What does this do for R. Soloveitchik? What does seeing it do for us?

In terms of what this does for R. Soloveitchik, the first thing we should note is that it serves as what he would call “a mattir,” a tool for rendering something permissible (a “permission structure” in the jargon of contemporary discourse). He takes things like the secular quest for knowledge or secular Zionism and renders them religious activities/phenomena by asserting that their underlying motivations are in fact religious. Religious individuals can therefore participate in those activities or collaborate with those movements without that compromising their religiosity.

Second, and something of an inversion of the former point, this theme may indicate that when R. Soloveitchik talks about “the quest for God,” he has something broader in mind than just the normal meaning of that phrase. If sacrificing for the land and attempting to understand “the Absolute” are both forms of searching for God, maybe God is more than just the Jewish deity who commanded the Jewish people to observe the Torah.

The final thing it does for R. Soloveitchik, I suspect, is that it simply reflects his understanding of reality, and his associated critique of modernity. He really thinks that people are driven by unconscious motivations for at least a significant portion of their activities. Moreover, he thinks denying or suppressing this fact is one of the fundamental tendencies of Western Modernity, and that it is of the utmost importance to restrain this tendency. Overconfidence in the totalizing power of rationality makes an idol of the human being—and of a mistaken understanding of the human being at that.

For interpreters of Rav Soloveitchik, it does a few things. One, the recurrence of the theme throughout R. Soloveitchik’s writings (across decades and genres) is itself notable. Second, making this explicit helps interpret the writings. For example, I have encountered pushback against my argument (in my Tradition essay) that Lonely Man of Faith describes faith as something “unconscious,” but given how willing Rav Soloveitchik is to appeal to this form of explanation, there is every reason to read his description of faith in this manner as well.

Similarly, the book as a whole should be interpreted from the perspective of a person who believes in the reality and significance of unconscious drives, which is to say, Adam the second. The Lonely Man of Faith is the sort of book Adam the second would write, not Adam the first. Adam the first thinks human beings can be fully explained as rational consumers. The Lonely Man of Faith knows what the person of faith, Adam the second, knows—what Rav Soloveitchik knows: that human beings are more complicated than that, that they are often driven by commitments that transcend calculations of logic and exchange.